Onesun Steve Yoo, Professor at UCL School of Management, has recently published a new book, Master Your Timeflow: A Modern Guide to Time Management. We sat down with him to discuss the long and unexpected journey behind the book, his concept of ‘timeflow’, and why many of our assumptions about productivity and time management are overdue for an update.

What inspired you to write Master Your Timeflow?

In some ways, the book came through an accidental journey. My PhD dissertation research, which I started in 2007-8, was originally about time management for entrepreneurs: how they should manage time to help their ventures grow. While there was some early interest, it took many years for that research to finally be published. During that long gap, I kept collecting notes about time from all sorts of places. Friends and family would send me articles and I’d jot things down myself from engineering fields, economics to self‑help books and everyday observations.

So, when I finally sat down and organised the notes I compiled over 10-15 years, I had over 40 pages of material. As I started to connect the ideas, I noticed there was a story here that hadn’t really been told before, especially around this idea of ‘timeflow’. That’s when I decided to formalise it into a book, even though I was writing very much part‑time, without any advance or fixed deadline.

Was part of your motivation to translate academic research into something more accessible?

Yes, very much so. My original background is in electrical engineering, where you naturally encounter ideas from physics, including Einstein’s theory of relativity. I realised that many of these ideas about time never really make it into public discussion, even though they’re incredibly relevant to how we live and work.

When you look at the history of time management, it largely stems from the nineteenth century, from figures like Frederick Taylor, who used pocket watches to measure productivity on factory floors. That legacy still shapes how we think about time today, for example, the fixed nine‑to‑five working day, and we often associate time management with disciplinary messages. I wanted to question that model and offer something more suited to modern life, drawing on both contemporary science and my own research.

How would you describe the core idea of the book?

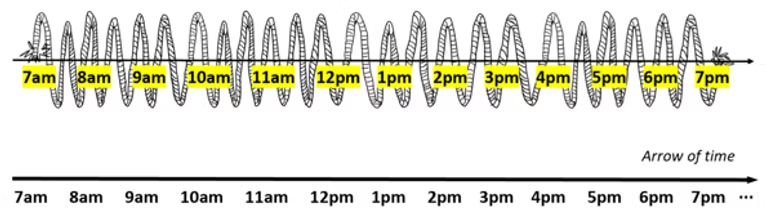

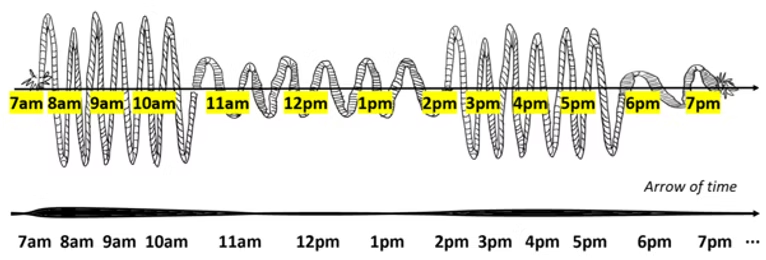

The central idea is that there is no single, absolute experience of time. We tend to think of time as something objective and seen from a third-person perspective as indicated on our mobile devices, but our lived experience is very different. Your time is very personal. Sometimes an hour feels long; sometimes it disappears in an instant. And it is possible for you to experience very different amount of time in a day than another person, even though the synchronised clock in our mobile devices says same amount of time has passed.

‘Timeflow’ is about how much time you actually experience from a first‑person perspective. Ideally, you want to experience more time during your waking hours. The book explores how you can structure your daily life and your longer‑term goals to increase your experienced time, rather than simply trying to cram more tasks into the clock hours available.

Who is the book for?

It’s designed to be widely applicable, for busy parents, budding entrepreneurs, seasoned executives, students, everyone that has experienced pressure from time. Everyone experiences time differently, but the underlying principles of timeflow apply across very different lives and circumstances.

If readers take away one practical idea from the book, what should it be?

I would say: become aware of your potential. The amount of time you experience is closely linked to what I describe as potential energy — the resources, systems, and environments around you that enable action. The more potential you have, the more time you will experience. So, before managing your time, you need to manage your potential.

Thinking in terms of potential brings lots of benefits because we are already used to it. For instance, we’re very familiar with financial potential: money represents future possibilities, and we borrow it with the understanding that it has to be paid back, often with interest. The idea of borrowing time is similar to borrowing money and I explain this in the book through the idea of borrowing potential. When you’re highly productive or energised, you’re effectively borrowing potential from your future self to experience more time now.

Did your own thinking about time change while writing the book?

Yes, particularly when I started trying to visualise the ideas. One moment that really shifted things for me was developing the illustrations, especially the idea of experienced time as something with ‘thickness’ of the time line. When time feels slow, it’s as if that line becomes thicker and richer; when time flies, it becomes thin.

Linking that visual idea to graphs of timeflow, where the area under the curve represents experienced time, was a turning point. At that point, I realised I had something concrete and original that I could explain clearly to others.

The book uses a lot of diagrams and illustrations. Is that part of your teaching style as well?

Absolutely. Visual explanations are incredibly powerful. These are complicated ideas, but a simple diagram can make them immediately understandable. I often say that if my family members can understand what I’m explaining, then I’m on the right track.

In that sense, the book is written very much as if I’m casually talking to my colleagues or engaged in a discussion with my students in the classroom, and that conversational tone seems to resonate with readers.

And what’s next for you after this book?

This is my first book, and initially I wrote it simply to bring a phase of my research journey to a close. But since publishing it, I’ve been encouraged by the feedback I’ve received. Readers often say it’s given them a completely new way to think about time.

My next step is to share the ideas more widely, starting with UCL students and the wider UCL community, but I would like to reach a broader audience as well. I’d like to continue the conversation around timeflow and explore how people can apply these ideas both in the short term, through daily habits, and in the long term, by reshaping the systems and goals that guide their lives.